Uh oh...

It appears that you're using a severely outdated version of Safari on Windows. Many features won't work correctly, and functionality can't be guaranteed. Please try viewing this website in Edge, Mozilla, Chrome, or another modern browser. Sorry for any inconvenience this may have caused!

Read More about this safari issue.

Just east of Ft. Smith, Franklin County is home to one of the most significant events in the history of American education. In 1954, county seat Charleston became the first school district in the former Confederate states to integrate all 12 grades. This is a point of pride to Charleston native Larry Lester, a Negro Leagues baseball historian now living in Kansas City. A commemorative plaque on the wall of Charleston High School honors his mother’s family, the Fergusons, who were some of the first African-American integrators.

Logan County is Franklin County’s southeast neighbor. No major, well-known event involving desegregation occurred within its borders. Its most famous native son is Jay Hanna “Dizzy” Dean, a St. Louis Cardinal immortal who in his 1930s heyday was considered the best pitcher in Major League baseball.

With his rural Dixie background, the tough-talking and tougher-playing Dean at first blush appeared to be a bigot. Early in his career he had no qualms, for instance, using racial slurs when referring to African Americans. Unquestionably, this man — who also said things like “A good bowl of Wheaties with bourbon can’t be beat” — lacked tact and verbal elegance.

But a deeper look shows Dean actually helped lay a foundation for the Civil Rights movement which transformed American society in the 1950s and 1960s. As the top white player in what was then the most glamorous position in segregated pro-American sports, Dean regularly competed against his black counterpart Leroy Robert “Satchel” Paige — the best pitcher in the professional Negro Leagues.

The promise of profit brought the duo together.

While many black and white Americans lived separate, parallel lives in the 1930s, especially in the South, baseball’s offseason provided an opportunity for the best of both worlds to clash. These games often happened on the “barnstorming” tours which were a regular part of American life in the early and mid-20th century.

The best professional baseball players of both colors, from Babe Ruth to Josh Gibson, took to the road each offseason to team up with other All-Stars, minor leaguers, college players and locals. The superstars attracted huge crowds and often made more money barnstorming than from their professional league salaries.

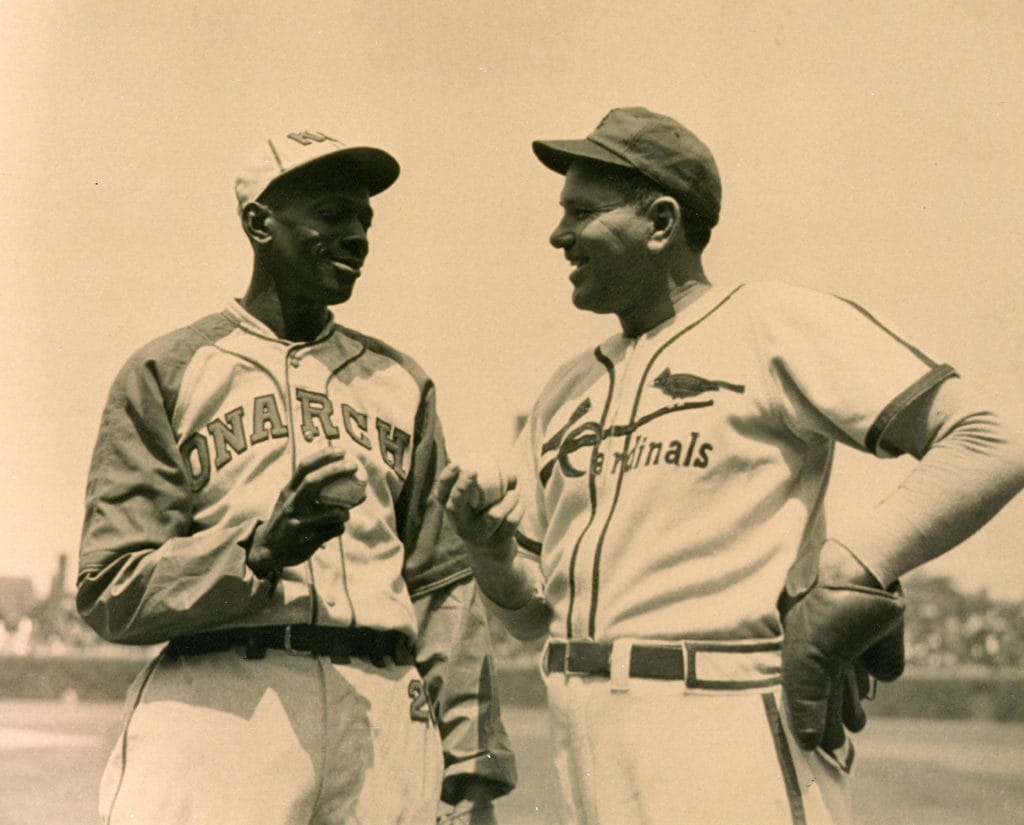

With his ability to dominate from the mound, Satchel Paige was the most highly sought barnstormer of them all. In the early to mid-1930s, Dean wasn’t far behind. On the circuit, each pitcher gathered his own same-race team of what promoters billed as “All-Stars” and staged multiple showdowns with each other.

The two men were, in many ways, alter egos — both “underfed, loose-jointed boys from Dixie whose down-home demeanor belied the sagacity of a Rhodes scholar and the cunning of a corporate titan,” Larry Tye wrote in Satchel: The Life and Times of an American Legend.

“Each preferred his nickname to his real one, and his own rules to his team’s, league’s or societies. Neither was the kind of guy to whom one would introduce his sister, although fathers and brothers were aching to meet them. Ol’ Diz pitched six of the Cardinals’ final nine games during the stretch drive in 1934, a work ethic only Ol’ Satch could match.”

In the 1930s, these rivals won and lost their share of showdowns, but they always won when it came to the gate. They generally pitched three innings, enough to satisfy fans and earn paychecks of $1,000 or more. Americans just couldn’t get enough of Paige v. Dean. Here, their opposing skin colors helped sustain interest, noted Larry Lester, a founder of the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum in Kansas City. “It draws more money if a heavyweight fight is between a heavyweight black champion and white champion.”

This has played out in real and cinematic boxing with the likes of Joe Louis v. Max Schmeling and Rocky Marciano v. Apollo Creed. This dynamic fueled a very marketable rivalry/friendship between NBA legends Larry Bird and Magic Johnson. Race division also underscored some of the intense media attention around quarterbacks Peyton Manning and Cam Newton before Super Bowl 50.

Paige and Dean ultimately developed a deep respect for each other’s skills, just as the aforementioned duos did. In 1934, Dean said “If Old Satchel and I played together, we’d clinch the pennant mathematically by the Fourth of July and go fishin’ until the World Series. Between us, we’d win 60 games.”

This was the year Dean pitched 30-7 and led the Cardinals to a World Series victory alongside his brother Paul “Daffy” Dean. His fame was at all-time high and, whether he meant to or not, he put cracks into segregationist walls speaking to millions of sports-crazy, impressionable baseball fans with words like that.

A few years later, Dean created another national stir when he wrote the following in a newspaper column: “A bunch of fellows gets in a barber session the other day and they start to argufy about whose [sic] the best pitcher they ever see, and some says Lefty Grove and Lefty Gomez and Walter Johnson and old Pete Alexander and Dazzy Vance. I know the best pitcher I ever see and its old Satchel Page, the big lanky colored boy. Say, old Diz is pretty fast back in 1933 and 1934, and you know my fastball looks like a change of pace alongside that little pistol bullet old Satchel shoots up the plate… It’s too bad those colored boys don’t play in the big leagues because they sure got some great players.”

It should be stressed Dean was not a social progressive. Indeed, he was widely perceived to be a redneck from the South. Yet here he was, near the height of the Jim Crow era, openly advocating for a level playing field with blacks. His words underscored an implicit message: If “everyday man” was fine with the idea, why shouldn’t other Southerners?

Dean suffered a severe arm injury in 1937. He was traded to the Chicago Cubs and by 1941 was out of the league. Yet even in retirement he still occasionally barnstormed with Paige.

They again made history together May 24, 1942, when Paige’s Kansas City Monarchs, one of the Negro Leagues’ most prestigious franchises, clashed with the Dizzy Dean All-Stars at the Chicago Cubs’ Wrigley Stadium.

The game was a hugely anticipated interracial matchup because Bob Feller, the Cleveland Indians young superstar pitcher then serving in the military, was supposed to play. Although Feller had to cancel, a crowd of about 30,000 people — mostly African Americans — still showed up to watch the Monarchs take 32-year-old Dean and his “All-Stars,” a mix of major leaguers, near-retirees and retirees.

The Monarchs, which featured fellow future Hall of Famer Hilton Smith and Conway County, Arkansas native Booker McDaniels, beat Dean’s team 3-1. Dean, meanwhile, pitched only an inning and retired his first three Monarchs. Chicago’s African-American community took great pride in this win even if Dean was mostly washed up by then, and Paige was winning most of their matchups at that point, anyway. The victory visually confirmed for Chicago’s black baseball fans what they had read about happening in other states throughout the previous decade — that their own race could hang with and beat big league stars.

It was as if, for years, “they’d been filing on a ‘segregation lock’ and then finally that big-time game happens, and it breaks the lock,” author Sherman Jenkins noted during the annual Jerry Malloy Negro League Conference earlier this month. “The lock is broken, and the floodgates begin to open and, as we say, the rest is history.”

Paige last played against Dean in 1945, but Dean’s most important work was by then long done. In the coming years, as a radio and TV sportscaster in St. Louis and New York, Dean saw much of the history he helped prompt unfold on the fields before him.

In 1947, Jackie Robinson became the first African American to play in the Major Leagues in the modern era. A year later, Dean’s old friend Satchel Paige joined the Cleveland Indians, becoming the first former Negro Leaguer to pitch in a World Series.

Jerry Malloy Negro League Conference, historian and author Larry Lester gave a powerful talk on “Why Black Baseball History Matters” on July 8, 2016, in Kansas City.

***

Speaking of World Series, how much of the Chicago Cubs’ 71-year curse is due to Mr. Wrigley’s inability to see what Dizzy Dean saw?

Photos courtesy of NoirTech Research.

Join the Conversation

Leave a Comment

One response to “Arkansan Dizzy Dean and Satchel Paige”

Leave a Reply

Leave a Reply

We do the work.

You check your email.

Sign up for our weekly e-news.

Get stories sent straight to your inbox!

Leave a Reply

Leave a Reply

[…] was a banner year for colorful brothers, Jay Hanna “Dizzy” Dean and his less boastful brother Paul Dee “Daffy” Dean. Born at Lucas in Logan County, the Deans […]