Uh oh...

It appears that you're using a severely outdated version of Safari on Windows. Many features won't work correctly, and functionality can't be guaranteed. Please try viewing this website in Edge, Mozilla, Chrome, or another modern browser. Sorry for any inconvenience this may have caused!

Read More about this safari issue.

Autumn is undeniably one of the best times of the year to take a drive through the Ozark Mountains. Better yet, lace up some hiking shoes, grab a water bottle, and find a trail to get lost on for a few hours. Okay, don’t get literally lost. My suggestion is to figuratively lose yourself in the forest; immerse yourself in the sights and sounds of the falling leaves, local wildlife, and breezes off a waterfall or stream. And while you’re at it, keep your eyes peeled for a long-lost tree that you could help bring back from the almost-extinct lists.

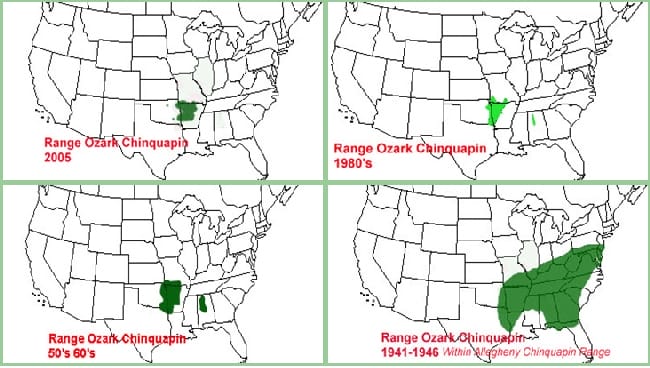

A century ago, the Ozark Chinquapin Tree (you might have heard it called an Ozark Chestnut) would have been a common sight as you wandered the forests of Arkansas. In 1907, its range covered our entire state and stretched up through Missouri and east through Kentucky , Tennessee, Alabama, Georgia, and into the Carolinas. The heat-tolerant hard-wood specimen was perfect for southern forests due to its fondness for the acidic, dry and rocky soils, as this type of terrain dominates the hilltops and slopes of the Ozark, Ouachita, Appalachian and Allegheny mountain ranges.

Early biologists and explorers reported finding specimens that towered over the understory at 65 feet in height and an impressive 2-3 feet in diameter. They were sought out by local wildlife like bears, squirrels and deer, and also harvested by humans as a sweetly-flavored, protein-packed staple during lean winter months. The wood was also rot-resistant, and was used often as ideal railroad ties and fence posts.

Today, unfortunately, as you hike the trails of the Ozarks, you will likely not have seen an Ozark Chinquapin in the wild, as logging practices and chestnut blight have wiped them almost entirely out of the forests. There are still stumps to be found, but the young trees that grow from those stumps eventually become blighted themselves, and succumb after only a few years.

But there is good news! The Ozark Chinquapin Foundation (OCF) was founded in 2007 by a man who had a vision of restoring the native tree to southern forests. Through his efforts, and those of hundreds of volunteers over the last decade, there is some light at the end of the tunnel. The OCF is attempting to establish a viable seed base through research and the manual cross-pollination of surviving trees. The goal is to develop a 100 percent pure Ozark Chinquapin that is blight resistant, and make the seeds available to anyone who wants to help restore the tree to its native forest range.

Benefits of restoring the Ozark Chinquapin include a more diverse ecology in our forests, which encourages and supports healthy wildlife populations.

One example of this loss is seen in the black bear population. There are a number of menu options for black bears in the Ozark forest, but they are highly dependent on the nut crop produced by oak, hickory and other fruiting trees. In Arkansas, black bears breed in late spring but the fertilized embryos do not implant into the uterus of the sow unless she is able to put on fall fat reserves from an ample nut crop. When the nut crop is weak, mama bear is not carrying much weight and she may lose all of her embryos. Not only do Ozark Chinquapin trees produce nutrient-packed nuts, but they produce them in large quantities – making it possible for all the animals of the forest to eat well over the winter.

Steve Chyrchel, Park Interpreter at Hobbs State Park & Conservation Area, is active in the work being done to restore the Ozark Chinquapin population to our local forests in Northwest Arkansas. It all started when a single mature specimen was found in their park.

“We found a fruiting Ozark chinquapin tree on the Park, and for years we sent all of the seed we could find to the Ozark Chinquapin Foundation for their use. We then were asked by the OCF if we would like to try cross-pollinating; taking some known pollen from trees with good genetics, and hand-pollinating the good tree that we had here at Hobbs State Park.”

Ozark Chinquapin trees need additional trees nearby to pollinate on their own, and according to Chyrchel, no one had ever been successful attempting a hand-pollination process of a single tree up to that time. But much everyone’s surprise and delight, they were able to harvest 32 viable seeds as a result of their efforts.

“This was a real breakthrough!” Chyrchel explained. “The president of the Ozark Chinquapin Foundation said that this was the most important thing to happen with the Ozark Chinquapin since the blight hit Northwest Arkansas in 1957.”

Going forward, other naturalists who were helping the OCF began following the lessons Chyrchel and his team had learned, and today volunteers are seeing more success with cross-pollinating the tree in other forested areas in Arkansas and elsewhere.

Two years after first planting, and the hillside has been transformed by native plant life, and volunteers recorded some trees over 6 feet tall!

Chyrchel is eager to spread the good news about the work being done at Hobbs State Park and by the OCF, and encourages anyone interested in helping, either individually or through their organization, to get involved in one of the following ways:

- Get the word out! Talk to others about this wonderful tree.

- Help locate fruiting Ozark chinquapin trees, and report them to the Ozark Chinquapin Foundation.

- Harvest seeds/nuts that you find and share them with the Ozark Chinquapin Foundation.

- If you have the right growing conditions, establish a test plot on your own or public property.

- Support the Ozark Chinquapin Foundation with an annual membership.

More information about the history of the Ozark Chinquapin tree and its future in Arkansas can be found at http://www.ozarkchinquapin.com/.

Join the Conversation

Leave a Comment

4 responses to “The Ozark Chinquapin Tree: Reviving a Native”

Leave a Reply

Leave a Reply

We do the work.

You check your email.

Sign up for our weekly e-news.

Get stories sent straight to your inbox!

Leave a Reply

Leave a Reply

[…] The Ozark Chinquapin Tree: Reviving a Native […]

[…] The Ozark Chinquapin Tree: Reviving a Native by Laurie Marshall […]

I just read an article about the Ozark Chinkapin in the American Frontiersman magazine that I really enjoyed.

I’ve seen the map of the area where they grow. Would the tree do well in northeast Oklahoma?

Where can I find chestnut seeds to plant?? I really want to grow several of these historic trees!