Uh oh...

It appears that you're using a severely outdated version of Safari on Windows. Many features won't work correctly, and functionality can't be guaranteed. Please try viewing this website in Edge, Mozilla, Chrome, or another modern browser. Sorry for any inconvenience this may have caused!

Read More about this safari issue.

As the daughter of a cotton farmer, cotton is a big part of my personal story. I still love to go home to the Delta during cotton harvest. Those flat white fields are as beautiful to me as any mountain vista or ocean view. While cotton production has declined through the years, cotton continues to be an important commodity, and Arkansas cotton is a big player in the world cotton scene.

In 2014, 335,000 acres of cotton were planted in the Natural State resulting in 820,000 bales being produced. According to Arkansas Farm Bureau, Arkansas’s cotton production ranks 3rd in the nation with 7% of the total U.S. crop and 4th in yield.

Did you know scientists found cotton bolls and pieces of cotton cloth in Mexico caves that dated back 7,000 years? And Jamestown colonists grew cotton in 1616. Cotton is one of the oldest heritage plants on earth.

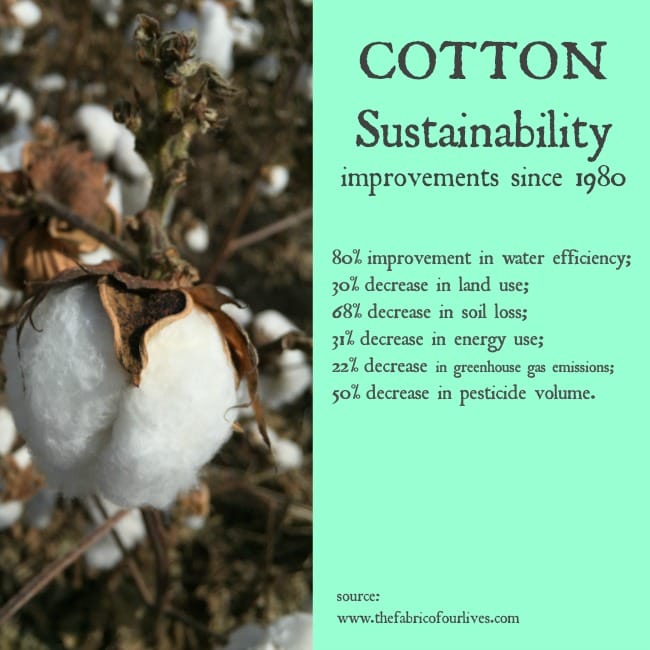

But cotton isn’t what it was when I was a child. It’s better. In the past thirty years, the cotton industry has made remarkable strides in lessening impact to the environment. And that’s a good thing.

When you think about the history of cotton ginning, do you think of Eli Whitney? We all learned about the father of the cotton gin in elementary school. His patent industrialized the process of removing seed from cotton. This allowed cotton production to grow rapidly throughout the southern United States during the 1800s. Cotton became King. Cotton also became indirectly woven into the issues central to the Civil War, as more cotton production meant more reliance upon slave labor. Later, during Reconstruction, sharecroppers farmed for cotton landowners in exchange for a portion of the crop. By the 1920s, it seemed that every small town in Arkansas had its own cotton gin.

In recent years, the number of Arkansas gins has decreased (86 in 2000 to 39 in 2013). The decline is due not only to the decline in cotton production, but also because of the increase in corn and soybean production, and overall business consolidation and efficiencies.

Driving along the flat highways and byways of the Delta, one can’t help but notice the massive gins jutting from the landscape. The largest cotton gin the Mid-South is Adams Cotton Gin located in Leachville (Mississippi County), Arkansas. When it was built in 1992, it was the largest gin in the world and is still one of the most technologically advanced.

If you’ve ever wanted to tour a cotton gin, here’s your chance. I recently spent time at the Lee Wilson & Company Gin (formerly named Willow Gin) in Wilson, Arkansas.

Let’s begin with the farm-to-gin process. When my Daddy was alive, cotton was hauled to the gin in cotton trailers. A few years later, cotton trailers were replaced with module builders. Module builders produced a loaf of bread-like bale in the field that was soon hauled to the gin.

Today, most cotton growers have moved to round bales. Round bales offer advantages over rectangular modules because the yellow plastic wrap protects the cotton. According to Wilson gin manager, Jim Johns, a round bale can sit in a field for at least a year before being ginned without showing any signs of deterioration.

Yes, my sister and I still love cotton. This picture shows the considerable size of round bales.

So what happens once the bale reaches the gin? Ginning is simple, really. By the strict definition, ginning is the process of separating the trash, debris, and cottonseed from the lint. Air moves the cotton through the gin. Blowers heat the cotton to help separate the debris, saws and combs separate the seed, a press bales it, and a machine wraps it in plastic. Each bale is bar coded and can be traced back to the individual farmer’s field.

The Lee Wilson & Company Cotton Gin is clean enough to eat off the floor.

The leftover “mote” is sold to a U. S. company that removes the remainder of the salvageable cotton and sells it overseas. If you buy inexpensive jeans, for example, you are likely buying this mote product rather than high quality cotton. Cottonseed meal and hulls are sold to dairy farmers as feed. Waste is minimal. And yes, the yellow plastic wraps are recycled.

A few interesting facts about cotton:

- American paper money is 75% cotton.

- The U.S. Cotton industry generates about 200,000 jobs annually.

- One bale of cotton produces 215 pairs of jeans.

- There are approximately 3,500 family cotton farms in the U.S.

- It takes 150 yards of cotton to make one baseball.

For more Arkansas farming facts, visit Arkansas Farm Bureau by clicking HERE.

We do the work.

You check your email.

Sign up for our weekly e-news.

Get stories sent straight to your inbox!

Like this story? Read more from Talya Tate Boerner

Do you set resolutions in January? For me, the beginning of a new year...

I always equate dragonflies to carefree summer days. My sister and I...

This spring, as you plan your Arkansas garden, why not plan for...

Join the Conversation

Leave a Comment